Ernest Hemingway didn’t finish A Farewell to Arms in one glorious sitting. Leonardo da Vinci didn't paint the Mona Lisa in a fevered night. And Beethoven, well, let's just say Ode to Joy didn’t spill from his genius like water from a tap. These masterpieces weren’t born from a single, uninterrupted stream of inspiration. In fact, they were held together by one crucial ingredient: the pause. The lingering space between what was done and what was left undone. That maddening whisper of unfinished work.

Take Hemingway, for instance. He was notorious for stopping in the middle of a sentence when the story was flowing, leaving himself hungry for the next round. He understood something most creatives miss: the power of not finishing. By leaving the thread dangling, the itch of the unresolved work haunted him—an itch that only scratched itself when he returned to the page. Unfinished work nags at your brain like a splinter buried too deep. It’s in that discomfort that your brain stays alive, crackling with ideas. It’s the Zeigarnik Effect. And for creatives, it’s a secret weapon, hiding in plain sight.

Bluma Zeigarnik was nobody’s household name. Not in the 1920s when she stumbled onto something that changed the way we think about thinking. In a noisy Vienna café, she noticed that waiters had an almost supernatural ability to remember orders—until they served them. The second the dishes hit the table, those orders evaporated from memory like yesterday’s rain. Unfulfilled orders? They stuck. They clung to the edges of the waiters’ minds until they were complete.

This wasn’t just about orders or waiters. Zeigarnik had cracked open a window into the creative mind. The unfinished holds power. It nags, tugs, and keeps us hooked until it’s done. For a painter, a writer, or any creative soul, this is where the magic lives: in that tension of the half-made, the half-seen. The work that’s done is dead, but the work unfinished? That’s alive.

The Why

The Zeigarnik Effect isn’t just some academic term tossed around by psychologists in sterile lecture halls. It's a phenomenon that taps directly into the heart of how we, as creatives, think and work. Simply put, it’s the idea that unfinished tasks stick in our minds like a song we can’t shake. Completed tasks? They fade, they lose their grip on us. But the things we leave dangling—those are the ones that keep us awake at night, gnawing at the edges of our thoughts, asking for closure.

For creatives, this is gold. It’s the restless energy that fuels your need to return to a project, the uncomfortable tension between the now and what could be. The brain doesn’t like loose ends, and when you leave something incomplete, it keeps working on it, like an engine humming quietly in the background. This can be a powerful tool if you know how to wield it.

Look at Picasso. He was notorious for starting multiple paintings at once, leaving canvases half-finished for days, sometimes weeks. Those half-finished pieces? They followed him. Haunted him. He’d return, brush in hand, vision clearer than when he left. And then there’s Maya Angelou, who’d famously abandon a paragraph mid-sentence when she felt her creativity flagging. Why? Because she knew that the pull of the unfinished sentence would bring her back to the page, ideas sparking fresh the next time she sat down.

The Zeigarnik Effect plays on our minds in a way that makes us uncomfortable with what’s incomplete. That discomfort drives us to seek resolution, to finish what we started. And it’s not just about art or writing—this is about every form of creativity. Filmmakers, designers, inventors—they all feel the pull of the half-made, the almost-there, the unfulfilled vision. It’s in the unfinished that possibilities linger, forcing the brain to explore new ideas, connections, and solutions.

The How

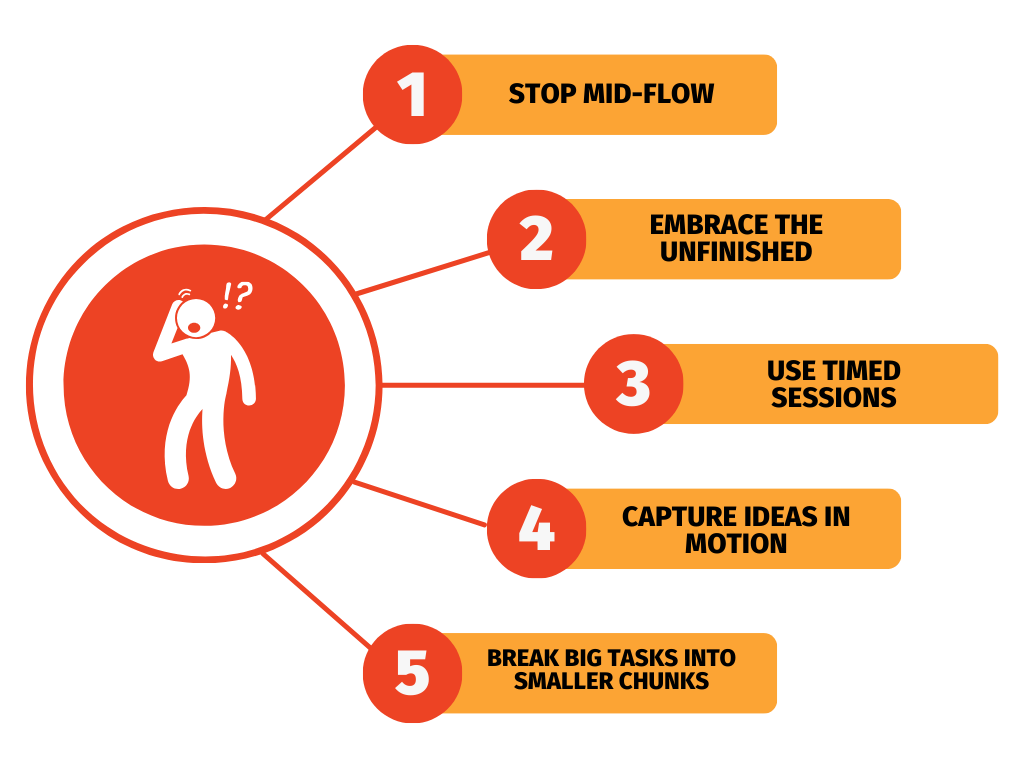

The beauty of the Zeigarnik Effect lies in its simplicity. It’s not a complicated hack requiring intense focus or hours of meditation. Instead, it’s a natural human instinct—an itch that won’t let you rest until you scratch it. For creatives, this is pure fuel. You can use this effect to keep your ideas simmering, your brain engaged, and your creativity flowing—even when you’re not actively working. Here’s how to tap into this underutilized tool and make it work for you:

- Stop mid-flow: When you’re in the zone, and everything’s clicking, stop. Pause when the ideas are still firing. This creates an unfinished mental loop that keeps your brain engaged even when you walk away.

- Embrace the unfinished: Don’t obsess over completing everything in one go. Leave parts of your project undone—whether it’s a painting, a story, or a design. Your brain will naturally keep working on it in the background.

- Use timed sessions: Set short, timed sessions for your creative work. When the timer’s up, stop—no matter where you are in the process. This reinforces the open loop and keeps you motivated to return.

- Capture ideas in motion: Keep a notebook or voice recorder handy. Ideas will strike when you least expect them—when you're not actively working, thanks to the lingering effect of unfinished tasks.

- Break big tasks into smaller chunks: By dividing a large project into smaller, incomplete pieces, you create multiple "open loops" that keep your brain returning to each part until the whole project comes together.

Tips and Tricks

The Zeigarnik Effect is powerful, but like any tool, it works best when wielded with intention. Here are some quick tips and tricks to maximize its creative potential:

- Start with a teaser: Begin your work with a rough sketch or draft to get the creative juices flowing, then stop before the ideas run dry.

- Leave clues for yourself: Write notes or leave open-ended sentences so you can easily jump back into the flow.

- Create visual reminders: Post sticky notes or visual cues to keep the unfinished work fresh in your mind.

- Vary your projects: Rotate between multiple projects to keep several open loops alive and maintain high creative energy.

- Make peace with imperfection: It’s okay if things aren’t perfect—embracing the unfinished leads to breakthroughs.

Mistakes to Avoid

While using the Zeigarnik Effect can be game-changing, there are pitfalls to avoid that could derail your progress:

- Stopping too soon: Don’t quit before you’ve gained any momentum. Give yourself enough to latch onto when you return.

- Finishing everything at once: Resist the urge to wrap up your work in a single sitting—it kills the lingering creative tension.

- Ignoring rest: Rest is crucial. Let the open loops sit for a while, but make sure you come back with fresh energy.

- Overcomplicating things: Don’t get bogged down by leaving too much unfinished. Find a balance between progress and leaving room for creative sparks.

- Avoiding deadlines: Unfinished work is powerful, but without deadlines, it can lead to procrastination and frustration.

The Silent Power of Walking Away

There’s an ancient myth that says once the Roman aqueduct builders set the final stone, they would deliberately chip away a corner, leaving the structure technically incomplete. Perfection wasn’t the goal—endlessness was. Like them, creatives often find their best work when they leave something unfinished, walking away before the last detail is in place. It’s counterintuitive, right? The common wisdom tells us to finish what we start, tie up loose ends, check the box. But the Zeigarnik Effect whispers something else: leave it open.

Walking away feels like failure to our perfectionist brains. The nagging urge to resolve that thing we started clings like static. But that discomfort? It’s where creativity thrives. When we walk away, we hand the reins to our subconscious. While you go about your day, run errands, talk to people, that unresolved project quietly loops in the background, waiting for you to return. Ideas simmer in that unresolved space. They brew and morph into something you couldn’t have come up with by staring at a blank screen or canvas.

Think of it like a seed you plant before you sleep. While you rest, roots grow. The moment you wake, it’s sprouted. When you sit back down to work, you find a new energy there, a new angle, a solution you didn’t see before. Walking away isn’t quitting—it’s strategic retreat.

It’s the space between where creation takes root.

Productive Discomfort: The Power of Staying Uncomfortable

Creativity isn’t born from comfort. It thrives in the tension, in the unsettled places where most people squirm and back away. This is the zone where ideas collide, where inspiration simmers beneath the surface. The Zeigarnik Effect reminds us that unfinished work has power, but it’s the discomfort that keeps us coming back. That nagging sense of “not done yet” is your ally—if you learn to embrace it.

Most people crave completion. We like checkboxes and finished projects, tidy little bows tied on the ends of things. But here’s the hard truth: completion can be a creativity killer. Once something is done, your mind moves on. The fire goes out. It’s in the productive discomfort of leaving things unresolved that your brain stays active, constantly toying with solutions, riffing on ideas, gnawing at the problem like a dog with a bone.

This discomfort, though unsettling, is where real growth happens. It’s the creative tension that artists like Hemingway thrived on. They understood that the irritation of an unfinished story, an unsolved problem, is precisely what keeps the mind engaged, even when it’s “off the clock.”

The trick? Don’t run from the discomfort. Lean into it. Sit with that unfinished project gnawing at the edges of your mind, knowing that in that discomfort lies the next great idea. It’s in the itch, the tension, the productive discomfort, where true creativity is forged.

Mental Models to Help You Leverage the Zeigarnik Effect

To fully harness the power of the Zeigarnik Effect, it helps to adopt mental models that keep your creative momentum alive. These frameworks will sharpen your focus and ensure you stay productive, even when you're not actively creating.

- The Endowment Effect: We value what we’ve already started more highly than what we haven’t. Use this to your advantage by starting projects, even if you leave them unfinished—your mind will naturally push you to return.

- Kaizen: Embrace incremental progress. Instead of aiming for perfection, leave room for small, constant improvements that keep your brain engaged in refining and revisiting the task.

- First Principles Thinking: Break down your project to its most basic elements. By doing so, you can focus on key pieces, leaving smaller tasks incomplete to keep your mental wheels turning.

- Chunking: Break work into digestible pieces. Small, unfinished chunks keep your mind engaged without overwhelming it.

- The Pomodoro Technique: Use time blocks to your advantage. By working in short, focused bursts (like 25 minutes), and then taking a break, you intentionally leave tasks incomplete, which keeps your brain engaged during the break.

- The 80/20 Rule (Pareto Principle): Focus on the vital 20% of a task that yields 80% of the results, leaving less crucial elements unfinished. Your mind will keep circling back to those small, open-ended details, often finding efficient ways to complete them later.

The Zeigarnik Effect isn’t just some quirky psychological finding—it’s a practical tool that can revolutionize how you approach creative work. By leaving projects unfinished, embracing the discomfort of open loops, and adopting mental models that keep your brain firing, you can tap into a steady stream of productivity and creative energy. In the end, it's the work that remains incomplete that keeps us coming back for more.